-

Duffy bowls New Zealand to T20 victory over Sri Lanka

Duffy bowls New Zealand to T20 victory over Sri Lanka

-

Turkey's pro-Kurd party to meet jailed PKK leader on Saturday

-

Gaza hospital shut after Israeli raid, director held: health officials

Gaza hospital shut after Israeli raid, director held: health officials

-

Surgery for French skier Sarrazin 'went well': federation

-

Mitchell, Bracewell boost New Zealand in Sri Lanka T20

Mitchell, Bracewell boost New Zealand in Sri Lanka T20

-

Kyrgios says tennis integrity 'awful' after doping scandals

-

S. Korean prosecutors say Yoon authorised 'shooting' during martial law bid

S. Korean prosecutors say Yoon authorised 'shooting' during martial law bid

-

Vendee Globe skipper Pip Hare limps into Melbourne after dismasting

-

Reddy's defiant maiden ton claws India back into 4th Australia Test

Reddy's defiant maiden ton claws India back into 4th Australia Test

-

Doubles partner Thompson calls Purcell doping case 'a joke'

-

Reddy reaches fighting maiden century for India against Australia

Reddy reaches fighting maiden century for India against Australia

-

Sabalenka enjoying 'chilled' rivalry with Swiatek

-

Political turmoil shakes South Korea's economy

Political turmoil shakes South Korea's economy

-

New mum Bencic wins first tour-level match since 2023 US Open

-

'Romeo and Juliet' star Olivia Hussey dies aged 73

'Romeo and Juliet' star Olivia Hussey dies aged 73

-

Brown dominates as NBA champion Celtics snap skid

-

Indian state funeral for former PM Manmohan Singh

Indian state funeral for former PM Manmohan Singh

-

France asks Indonesia to transfer national on death row

-

Ambitious Ruud targets return to top five in 2025

Ambitious Ruud targets return to top five in 2025

-

Late bloomer Paolini looking to build on 'amazing' 2024

-

Australia remove Pant, Jadeja as India reach 244-7 at lunch

Australia remove Pant, Jadeja as India reach 244-7 at lunch

-

Scheffler sidelined by Christmas cooking injury

-

Rice seeks trophies as Arsenal chase down 'full throttle' Liverpool

Rice seeks trophies as Arsenal chase down 'full throttle' Liverpool

-

Trump asks US Supreme Court to pause law threatening TikTok ban

-

Arsenal edge past Ipswich to go second in Premier League

Arsenal edge past Ipswich to go second in Premier League

-

LawConnect wins punishing and deadly Sydney-Hobart yacht race

-

Ronaldo slams 'unfair' Ballon d'Or result after Vinicius snub

Ronaldo slams 'unfair' Ballon d'Or result after Vinicius snub

-

Several wounded N.Korean soldiers died after being captured by Ukraine: Zelensky

-

Fresh strike hits Yemen's rebel-held capital

Fresh strike hits Yemen's rebel-held capital

-

Netflix with Beyonce make splash despite NFL ratings fall

-

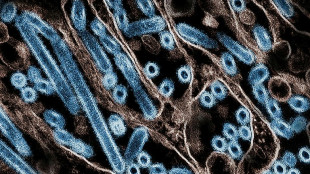

Bird flu mutated inside US patient, raising concern

Bird flu mutated inside US patient, raising concern

-

Slovakia says ready to host Russia-Ukraine peace talks

-

Maresca challenges Chelsea to react to Fulham blow

Maresca challenges Chelsea to react to Fulham blow

-

Tech slump slays Santa rally, weak yen lifts Japan stocks higher

-

Test records for Zimbabwe and Williams as Afghanistan toil

Test records for Zimbabwe and Williams as Afghanistan toil

-

LawConnect wins punishing Sydney-Hobart yacht race

-

Barca's Yamal vows to 'come back better' after ankle injury

Barca's Yamal vows to 'come back better' after ankle injury

-

Olmo closer to Barcelona exit after registration request rejected

-

Watching the sun rise over a new Damascus

Watching the sun rise over a new Damascus

-

Malaysia man flogged in mosque for crime of gender mixing

-

Montenegro to extradite crypto entrepreneur Do Kwon to US

Montenegro to extradite crypto entrepreneur Do Kwon to US

-

Brazil views labor violations at BYD site as human 'trafficking'

-

No extra pressure for Slot as Premier League leaders Liverpool pull clear

No extra pressure for Slot as Premier League leaders Liverpool pull clear

-

Tourists return to post-Olympic Paris for holiday magic

-

'Football harder than Prime Minister' comment was joke, says Postecoglou

'Football harder than Prime Minister' comment was joke, says Postecoglou

-

Driver who killed 35 in China car ramming sentenced to death

-

Bosch gives South Africa 90-run lead against Pakistan

Bosch gives South Africa 90-run lead against Pakistan

-

French skier Sarrazin 'conscious' after training crash

-

NATO to boost military presence in Baltic after cables 'sabotage'

NATO to boost military presence in Baltic after cables 'sabotage'

-

Howe hopes Newcastle have 'moved on' in last two seasons

| RBGPF | 100% | 59.84 | $ | |

| VOD | 0.12% | 8.43 | $ | |

| BTI | -0.33% | 36.31 | $ | |

| RIO | -0.41% | 59.01 | $ | |

| NGG | 0.66% | 59.31 | $ | |

| GSK | -0.12% | 34.08 | $ | |

| SCS | 0.58% | 11.97 | $ | |

| BP | 0.38% | 28.96 | $ | |

| RYCEF | 0.14% | 7.27 | $ | |

| CMSD | -0.67% | 23.32 | $ | |

| BCC | -1.91% | 120.63 | $ | |

| AZN | -0.39% | 66.26 | $ | |

| BCE | -0.93% | 22.66 | $ | |

| CMSC | -0.85% | 23.46 | $ | |

| RELX | -0.61% | 45.58 | $ | |

| JRI | -0.41% | 12.15 | $ |

Birds, beetles, bugs could help replace pesticides: study

Natural predators like birds, beetles and bugs might be an effective alternative to pesticides, keeping crop-devouring pests populations down while boosting crop yields, researchers said Wednesday.

Pests are responsible for around 10 percent -- or 21 million tonnes -- of crop losses every year, but controlling them has led to the widespread use of chemical pesticides.

Could birds, spiders and beetles among other invertebrate predators do the job as well?

Researchers in Brazil, the United States and the Czech Republic analysed past research on predator pest control and found that they helped reduce pest populations by more than 70 percent, while increasing crop yields by 25 percent.

"Natural predators are good pest control agents, and their maintenance is fundamental to guaranteeing pest control in a future with imminent climate change," lead author Gabriel Boldorini, a PhD student at the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco in Brazil, told AFP.

Although the researchers did not directly compare the effectiveness of invertebrates versus pesticides, he said, the damage that pesticides cause to ecosystems and biological control was well documented, from biodiversity loss and water and soil pollution to human health risks.

The researchers found that predators were more effective at pest control in regions with greater rain variability -- which is expected to increase because of climate change.

The researchers were also surprised to find that having a single species of natural predator was as effective as having multiple species, Boldorini said.

"Generally speaking, the more species there are, the better ecosystems function. But there are exceptions," he said, adding that a single species could do the job just as well.

Climate change and rising carbon dioxide levels affect both crop yield and pest dynamics by expanding the distribution of pests and increasing their survival rates.

Meanwhile, other studies have shown that invertebrates vital for ecosystem health are suffering a rapid decline globally.

Boldorini said the conservation of invertebrates "guarantees pest control and increased productivity, without damaging ecosystems".

J.Pereira--PC