-

At least 32 die in bus accident in southeastern Brazil

At least 32 die in bus accident in southeastern Brazil

-

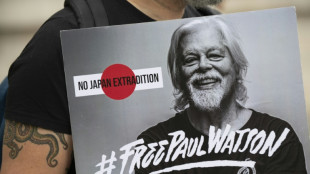

Freed activist Paul Watson vows to 'end whaling worldwide'

-

Chinese ship linked to severed Baltic Sea cables sets sail

Chinese ship linked to severed Baltic Sea cables sets sail

-

Sorrow and fury in German town after Christmas market attack

-

Guardiola vows Man City will regain confidence 'sooner or later' after another defeat

Guardiola vows Man City will regain confidence 'sooner or later' after another defeat

-

Ukraine drone hits Russian high-rise 1,000km from frontline

-

Villa beat Man City to deepen Guardiola's pain

Villa beat Man City to deepen Guardiola's pain

-

'Perfect start' for ski great Vonn on World Cup return

-

Germany mourns five killed, hundreds wounded in Christmas market attack

Germany mourns five killed, hundreds wounded in Christmas market attack

-

Odermatt soars to Val Gardena downhill win

-

Mbappe's adaptation period over: Real Madrid's Ancelotti

Mbappe's adaptation period over: Real Madrid's Ancelotti

-

France's most powerful nuclear reactor finally comes on stream

-

Ski great Vonn finishes 14th on World Cup return

Ski great Vonn finishes 14th on World Cup return

-

Scholz visits site of deadly Christmas market attack

-

Heavyweight foes Usyk, Fury set for titanic rematch

Heavyweight foes Usyk, Fury set for titanic rematch

-

Drone attack hits Russian city 1,000km from Ukraine frontier

-

Former England winger Eastham dies aged 88

Former England winger Eastham dies aged 88

-

Pakistan Taliban claim raid killing 16 soldiers

-

Pakistan military courts convict 25 of pro-Khan unrest

Pakistan military courts convict 25 of pro-Khan unrest

-

US Congress passes bill to avert shutdown

-

Sierra Leone student tackles toxic air pollution

Sierra Leone student tackles toxic air pollution

-

German leader to visit site of deadly Christmas market attack

-

16 injured after Israel hit by Yemen-launched 'projectile'

16 injured after Israel hit by Yemen-launched 'projectile'

-

Google counters bid by US to force sale of Chrome

-

Russia says Kursk strike kills 5 after Moscow claims deadly Kyiv attack

Russia says Kursk strike kills 5 after Moscow claims deadly Kyiv attack

-

Cavaliers cruise past Bucks, Embiid shines in Sixers win

-

US President Biden authorizes $571 million in military aid to Taiwan

US President Biden authorizes $571 million in military aid to Taiwan

-

Arahmaiani: the Indonesian artist with a thousand lives

-

Indonesians embrace return of plundered treasure from the Dutch

Indonesians embrace return of plundered treasure from the Dutch

-

Qualcomm scores key win in licensing dispute with Arm

-

Scientists observe 'negative time' in quantum experiments

Scientists observe 'negative time' in quantum experiments

-

US approves first drug treatment for sleep apnea

-

US drops bounty for Syria's new leader after Damascus meeting

US drops bounty for Syria's new leader after Damascus meeting

-

Saudi man arrested after deadly car attack on German Christmas market

-

'Torn from my side': horror of German Christmas market attack

'Torn from my side': horror of German Christmas market attack

-

Bayern Munich rout Leipzig on sombre night in Germany

-

Tiger in family golf event but has 'long way' before PGA return

Tiger in family golf event but has 'long way' before PGA return

-

Pogba wants to 'turn page' after brother sentenced in extortion case

-

Court rules against El Salvador in controversial abortion case

Court rules against El Salvador in controversial abortion case

-

French court hands down heavy sentences in teacher beheading trial

-

Israel army says troops shot Syrian protester in leg

Israel army says troops shot Syrian protester in leg

-

Tien sets-up all-American NextGen semi-final duel

-

Bulked-up Fury promises 'war' in Usyk rematch

Bulked-up Fury promises 'war' in Usyk rematch

-

Major reshuffle as Trudeau faces party pressure, Trump taunts

-

Reggaeton star Daddy Yankee in court, says wife embezzled $100 mn

Reggaeton star Daddy Yankee in court, says wife embezzled $100 mn

-

Injured Eze out of Palace's clash with Arsenal

-

Norway's Deila named coach of MLS Atlanta United

Norway's Deila named coach of MLS Atlanta United

-

Inter-American Court rules Colombia drilling violated native rights

-

Amazon expects no disruptions as US strike goes into 2nd day

Amazon expects no disruptions as US strike goes into 2nd day

-

Man Utd 'more in control' under Amorim says Iraola

Ecuadoran toad breaks its silence after 100 years

Ecuadoran biologist Jorge Brito was trekking through the forest when he heard what he thought was the chirp of a cricket.

What he found changed a century of scientific belief.

"At first I thought it was some sort of cricket out there vocalizing, but then I paid attention," said Brito, from Ecuador's national biodiversity institute.

It was, in fact, a type of brown toad with rough skin called Rhinella festae that has a prominent nose and had been considered mute since it was first discovered 100 year ago.

"While it did not inflate its vocal sack, you could see a small flicker" on its chin, said Brito.

He caught it and took it to a laboratory to study with his colleague Diego Batallas.

"The first time I heard it, I said: Wow, that's not the sound of a toad, it's like a little bird," Batalla told AFP.

The toad, which measures between 45 and 68 centimeters in length, lives in the mountainous Ecuadoran regions of Cutucu and Condor, extending over the border into the Amazonian region of Peru.

The discovery was first reported in February in Neotropical Biodiversity magazine, where Brito and Batallas described the sound made by the toad.

"It is the first time this unique song of the Rhinella festae has been recorded and it's surprising because it shouldn't sing," Batallas told AFP.

The toad does not have the vocal sack that allows most amphibians to amplify their calls so that they can be heard up to one kilometer away.

"The fact that this species can sing (without the vocal sack) makes it unique," added Batallas, who used to sing in a choir.

Batallas said that the faint sound emitted by the Rhinella festae demonstrates that some species of amphibians could have evolved in such a way -- perhaps as an anti-predator measure -- as to "not need their song to be heard very far away."

In the case of the Rhinella festae, it emits a sound as a greeting, whereas other species of toad croak as part of a mating ritual or as a warning.

"It's a very subtle sound and very difficult to hear in nature."

Ecuador has registered 658 different species of amphibians, of which 623 are toads or frogs and almost 60 percent of those are at risk or in danger of disappearing.

Only Brazil and Colombia have more species of amphibians than Ecuador.

N.Esteves--PC